By: Song Lee

Volume X – Issue II – Spring 2025

I. INTRODUCTION

Few Supreme Court decisions in recent history have struck higher education with the force of Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. Harvard (2023). The Supreme Court trampled decades of precedent with one powerful blow, leaving college admissions offices scrambling in its wake. To trace the path our nation has taken to today’s legal battleground on education, one must follow the court’s reasoning. Amid Supreme Court cases such as Brown v. Board of Education during the Civil Rights Movement, President John F. Kennedy passed the 1961 directive to “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.” [1] In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson expanded these legal protections throughout the “private sector (Title VII) and in federally funded programs (Title VI),” further putting forth the Equal Employment Opportunity executive order prohibiting federal contractors employee discrimination. [2] Thus, affirmative action came from the federal government’s response to racial discrimination of the mid 1900s.

Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. Harvard (2023) revolves around the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause. This law was established after the Civil War, prohibiting states from denying any “the equal protection of the laws” on the basis of “race or color.” [3] In the words of Senator Jacob Howard, this equality principle was to eradicate racial discrimination and provide the “same rights and the same protection before the law,” irrespective of wealth or status. [4] Despite the passage of protective legislation, racism continued to permeate through the nation’s legal system.

After decades of legal battles distinguishing impermissible racial quotas from permissible racial “plus factor”considerations in admissions, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard marked a sharp constitutional reversal. Instead of moving toward a more inclusive future, this ruling marks a regression that pulls the nation away from decades of hard-fought civil rights gains toward equal opportunity.

II. RELEVANT CASES

A series of legal cases demonstrate the evolution of affirmative action in college admissions for Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard.

In Regents of Univ. of California v Bakke (438 US 265 [1978]), the University of California, Davis Medical School's admissions program was scrutinized under the California Constitution, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. [5] Allan Bakke, a white male applicant who was rejected from the school, sued the admissions program for racial discrimination. [6] The Supreme Court held that the admissions program unlawfully used “explicit racial classification,” but did not eliminate “any consideration of race” entirely, as racial background could be considered if it was simply a factor among other characteristics. [7] A “target-quota” of a set number of minority students is unlawful, but racial background can be a “plus” when considering other “combined qualifications.” [8] Thus, the court’s final decision on Equal Protection Clause legality was divided—while race could be a factor when considered among others, it could not be the sole determining element of admissions.

The Supreme Court applied the prior rationale in Grutter v. Bollinger (539 US 306, 311 [2003]) with University of Michigan Law School, where the weight of race as a factor in admissions decisions was significantly reduced. [9] Again, race was only to be considered a “plus” alongside the rest of students’ applications, but if racial minorities were plugged into quotas or different “admissions tracks” and “insulate” racial groups” the admissions program would be unlawful. [10] Thus, Grutter v. Bollinger argued that race-based admissions systems like the University of Michigan’s have three primary flaws: first, they can result in “stereotyping”; second, they allow race to devolve into a “negative” basis for discrimination rather than Regents of the University of California v. Bakke’s aforementioned “plus”; third, they fail to indicate a foreseeable end. [11] Justice Roberts opined that affirmative action programs should be created with a “termination point” or end because they inherently function counter to the Equal Protection Clause. [12] However, race can be considered “one factor among many” in a holistic review process. [13] A little over a decade after the Grutter v. Bollinger decision, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. Harvard implicitly overturned this precedent with its 6-3 majority. [14]

The current president of the SFFA, white conservative legal strategist Edward Blum. Prior to taking on the 2023 case, Blum represented white student Abigail Fisher in the Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin case on the basis of reverse discrimination and failed to win the case. This case differed from Grutter because of the Top Ten Percent Plan, a Texan legislative directive enforced during the case in response to Hopwood v. Texas. [15] Unlike the admissions system in Grutter, the Plan only implemented “race-conscious holistic review” to the bottom majority of the class, while saving a guaranteed spot for any highschool student graduating at the top ten percent applying to a public state university. [16] University officials elucidate that Fisher did not even fit within the top ten percent category, as her “grade point average (3.59) and SAT scores (1180 out of 1600)” were insufficient compared to other applicants and would not have guaranteed an acceptance anyway. [17] As Fisher failed to reach the top 10% of her class, she was rightfully evaluated under holistic review and rejected. As the university demonstrated “goodfaith efforts” to comply with the law and Fisher failed to show by a preponderance of the evidence that the university denied her equal treatment, the race-conscious admissions program was found to be lawful under the Equal Protection Clause. [18] After this unsuccessful case, Blum’s legal strategy in dismantling affirmative action pivoted—in his words, he realized he now “needed Asian Plaintiffs.” [19]

III. CASE BACKGROUND

Harvard University, an Ivy League institution, is globally recognized for its rich history as the “first college in the American colonies” and for its competitive selection process. [20] For the class of 2028, only 1,970 students were admitted out of the 54,008 applicants. [21] Within this applicant pool, Asian Americans made up more than all of the other minority groups combined, which included African American or Black, Hispanic or Latino, Native American, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander. [22] However, the unmentioned proportion of white students constitutes the majority of all acceptances.

The majority decision in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v President & Fellows of Harv. Coll., (600 U.S. 181 [2023]) found that Harvard’s admissions process was heavily intertwined with race. Harvard’s admissions process includes first reader ratings, subcommittees based on geographic area, a full committee meeting, and a final stage of eliminating students in what is called its “lop” process. [23] The first two steps “can and do take an applicant’s race into account,” the third considers “relative breakdown of applicants by race,” and the fourth considers race among other factors. [24]

The University of North Carolina (“UNC”) similarly has a rich history as the first public university of America, with a selective admissions process that accepts 4,200 of 43,500 applicants. [25] UNC’s process is also heavily influenced by race—in the first read, applicants are scrutinized with their racial background, and the subsequent school group review of committees thus takes race into account. [26] Throughout the litigation period, the court found a pattern in UNC admissions (the details of which warrant a separate discussion) non-Asian underrepresented minorities were more likely to have higher personality ratings but lower academic, extracurricular, and essay ratings than Asians. [27]

The petitioner of Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v President & Fellows of Harv. College is a nonprofit organization named Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA). [28] The SFFA’s mission statement declares that “race and ethnicity should not …harm or help …gain admission to a competitive university.” [29] The SFFA sued the UNC's and Harvard’s admissions programs on November 17th, 2014. [30] In 2023, the Supreme Court majority held that both schools illegally discriminated against Asian American college applicants under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. [31] This Supreme Court case overturned legal precedent, inhibiting universities from establishing “race-conscious admissions.” [32] Justices Sotomayor and Jackson dissented, arguing that the majority’s decision is divergent from the historical purpose of the Equal Protection Clause and Title VI—to bring “greater equality to African Americans.” [33] By enforcing racially blind admissions, the court would deconstruct the Constitution’s promise for equal protections and deepen systemic racism in educational institutions. [34]

IV. LEGAL REASONING

In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College (2023), the rationale against Harvard University and UNC was based on the three-pronged Grutter rationale—the admissions program was ambiguous, employed race as a negative and a stereotype, and failed to demonstrate a termination point. [35]

First, the majority held that the Respondents failed to demonstrate that their admissions programs warranted race-based admissions, as the justification for considering race was insufficient, vague, and unmeasurable. Harvard maintains idealistic goals to create “future leaders” and “better educating its students through diversity,” and UNC vouches to promote the “robust exchange of ideas.” [36] However, the majority argues that these standards are unquantifiable and ambiguous metrics of success. [37] Even if these standards are measured, courts are unable to recognize when they have been sufficiently achieved, creating no end point. [38] The various racial categories themselves range from imprecise to overbroad to underinclusive, undermining true diverse representation. For example, the classification “Asian” is arguably too broad, grouping all East Asians and South Asians together. [39] Thus, the majority argues the universities’ goals are insufficient justifications to implement race-based admissions.

Second, the Equal Protection Clause holds that it is unconstitutional for race to be used as a “negative” or a “stereotype.” [40] Since “college admissions are zero-sum,” any factor that benefits some but is a “negative” for the rest, decreasing their acceptance rate—the majority thus points to the “11.1% decrease in the number of Asian-Americans admitted to Harvard.” [41] The majority further draws from Bakke in the race qua race argument or “race for race’s sake,” as the two schools generalize that “a black student can usually bring something that a white person cannot offer-” a stereotype that works directly against the “core purpose of the Equal Protection Clause.” [42] In other words, the court found it was an unlawful stereotype to maintain that a student was merely a valuable contributor to the student body for their racial background.

Third, the majority held that the Respondents failed to demonstrate that their admissions programs had a perceptible termination point to warrant race-based admissions. [43] The respondent claimed that the admissions programs should terminate when there was “meaningful representation and meaningful diversity,” but this metric fails to involve a “numerical benchmark.” [44] The majority found that the “tight band” of racial balancing or “quotas” of yearly incoming applicants were unconstitutional as they merely reduced individuals to “components of a racial, religious, sexual, or national class” and must end. [45]

The dissent claimed the legal precedent of Bakke, Grutter v. Bollinger, and Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin were all extensions of Brown v. Board of Education, demonstrating that race-conscious admissions remain constitutional. [46] Race-blind admissions, they argue, would be “superficial… in an endemically segregated society” where race has historically mattered. [47] By removing racial considerations in an admissions program, the court was allowing racism to run rampant into the education system. As education has historically been the crucial “foundation of our democratic government and pluralistic society” and a determinant in the enforcement of structural racism, this majority decision would have an unfathomably large impact. [48] The dissent points to both UNC’s and Harvard’s “sordid legacies of racial exclusion” ranging from slavery to eugenics to demonstrate this notion. [49] In order to truly achieve the purpose of the Equal Protection Clause, Justice Sotomayor, with whom Justice Kagan and Justice Jackson join, argued that institutions must make “room for underrepresented groups that for far too long were denied admission” under the law. [50]

V. APPLICATION

In the wake of Students for Fair Admissions, universities must navigate a legal landscape that significantly limits race-conscious policies. Institutions like Cornell University are no exception.

Cornell touts itself as a “private, Ivy League university” and “the land-grant university for New York State.” A year before the adoption of the Equal Protection Clause in early 1867, Ezra Cornell promoted university education for men and women alike, “so that they [women] may have the same opportunity… to become wise and useful to society that the boys are”. [51] Thus, from Cornell University’s founding in 1868, Ezra Cornell “radically” claimed he wished to create “an institution where any person can find instruction in any study—” a motto that Cornell continues to tout as its founding principle. [52] This principle grew alongside the university throughout its earliest history. Co-founder Andrew Dickinson White claimed the university shall accept students of color even if the white students “asked for dismissal on this account,” and the school accepted its first students of African and Japanese descent, William Bowler and Kanaye Nagasawa respectively. [53] Cornell has thus long taken pride in being a radical institution that strives to lead in progressive thought and action.

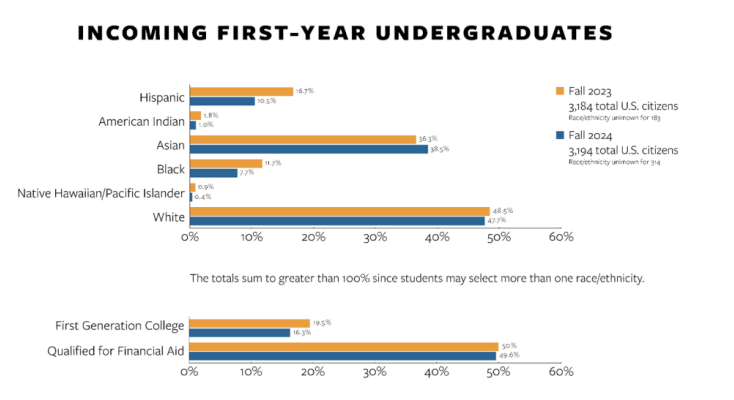

Cornell University complied with the SFFA case court proceedings. Admissions Committees evaluating the class of 2028, the first since this case ruling, did not consider racial and ethnic background, which was correlated with an “overall decline in the racial diversity of our entering class.” [54] The below chart demonstrates the changes in Cornell University’s racial and ethnic background as self-reported by American citizens without separately accounting for multiracial students.

[55]

Although this analysis simply accounts for one year, one can already witness the significant drop in Black and Hispanic students, the smaller increase in Asian students, and the smaller decrease in American Indian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Isalnder, and White Americans.

In response to SFFA’s claims, a 2024 study by Cornell researchers found that removing affirmative action to enforce a “race-blind” admissions process would hurt diversity while failing to improve the academic performance of a university. [56] By removing race in the Machine Learning Baseline model, the amount of underrepresented minorities “in the top-ranked pool drops to 20%—a 62% reduction” which was not accompanied with significant improvement in “standardized test percentiles.” [57] Furthermore, removing race from admissions did not fix the “arbitrary outcomes” of college admissions due to its fundamental problems of “(1) limited space at selective American colleges and (2) inherent randomness in the admissions process.” [58] Their research thus found that the SFFA’s removal of affirmative action would decrease diversity, fail to improve the academic quality of universities, and still result in top applicants not getting into top institutions due to the arbitrary nature of the process.

This year, this affirmative action case has constantly resurfaced with respect to Cornell’s policy and funding. From the start of Donald Trump’s second presidential term in January, one of his first executive orders, “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity” was to eliminate diversity programs and hold “federal contractors and subcontractors responsible for taking “affirmative action.” [59] Cornell was poised to lose “substantial federal funding through grants in contracts,” which had amounted to “$157 million in state and federal funding for research, grants and student scholarships” the previous year. [60] Furthermore, on February 14th, 2025, the Acting Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights of the United States Department of Education, Craig Tranor claimed that the Supreme Court’s holding should be “broadly” applied, removing race-based “admissions, hiring, promotion, compensation, financial aid, scholarships, prizes, administrative support, discipline, housing, graduation ceremonies.” [61] In this famed “Dear Colleague” letter, Trainor claimed that:

“All educational institutions are advised to: (1) ensure that their policies and actions comply with existing civil rights law; (2) cease all efforts to circumvent prohibitions on the use of race…(3) cease all reliance on third-party contractors, clearinghouses, or aggregators that… circumvent prohibited uses of race. Institutions that fail to comply with federal civil rights law may, consistent with applicable law, face potential loss of federal funding.” [62]

In response to this strongly worded directive which vaguely opposed facially “neutral” programs “motivated by racial considerations,” institutions nationwide were pressured to eliminate race-conscious admissions practices. [63]

These changes put Cornell’s admissions policy, race-based courses in “history, art, and government,” and a multitude of its affinity groups on the chopping block. [64] As the Cornell Daily Sun highlights, Cornell University changed its Equal Education and Employment Opportunity Statement, removing mention of DEI, discrimination resources, and affirmative action on March 19th. [65] The Board of Trustees reviewed to approve a new statement on March 21st, restoring everything but affirmative action. [66] In the words of a Cornell University spokesman, this change was to “remove affirmative action requirements for federal contractors," in line with Trump’s aforementioned executive order. [67]

The Students for Fair Admission v Harvard case is transforming Cornell, overturning policy amid rampant discrimination claims. On March 27th, Stanley Zhong and his father sued Cornell University with Students Who Oppose Racial Discrimination (SWORD), claiming racial discrimination. [68] Zhong alleged that Cornell, alongside other prominent universities, is violating Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. [69] Despite his “3.97 unweighted GPA, a 1590 SAT score and significant achievements in computer science,” he was rejected from 16 schools, but he “received a full-time job offer from Google for a position typically requiring a Ph.D. or equivalent experience” promptly afterwards which he could turn to as an alternative. [70] This legal action was not an isolated incident—it was emblematic of a broader national reckoning sparked by the 2023 Supreme Court decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard. In the relevant words of Hasan Minhaj at the end of his “Affirmative Action” episode on The Patriot Act:

“If you are willing to act like racism isn’t a thing, team up with lawyers, and then take it to the courts when you don’t get your way…you truly are an American, You just happen to be the worst kind.” [71]

VI. FUTURE IMPLICATIONS

The Cornell Undergraduate Law & Society Review proudly upholds the legacy of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (“RBG”), so it is only fitting to draw from her legal intellect. As RBG noted in a 2009 commencement address, affirmative action holds the potential to decrease “inequality, foster diversity, and promote the economic and social well-being of people raised in unprivileged communities” and “effective participation” from all citizens is “essential if the dream of one Nation, indivisible, is to be realized." [72] RBG’s hopeful message echoed Justice O’Connor’s argument in Grutter. [73] The disintegration of affirmative action does not indicate equal college admissions. Economists Raj Chetty and David J. Deming of Harvard University and John N. Friedman of Brown University conducted a 2023 study on Stanford, MIT, Duke, the University of Chicago, and the Ivy League schools, America’s prestigious private universities accounting for “less than half of 1% of Americans.” [74] Their study found that America's wealthiest top one percent was “more than twice as likely” to attend these universities as middle-class students despite having the exact same academic credentials in terms of SAT and GPA. [75] With legacy admissions, the wealthy cement their elite status, standing against the constitutional purpose of the Equal Protection Clause. The twelve universities of the study were significantly correlated with career success, consisting of over “10% of Fortune 500 CEOs, a quarter of U.S. Senators, half of all Rhodes scholars, and three-fourths of Supreme Court justices appointed in the last half-century.” [76] By maintaining legacy admissions, institutions like Cornell provide unequal opportunity. The Cornell University Student Assembly has made efforts to end legacy admissions after the Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v President & Fellows of Harv. College case with the Resolution 68 resolution proposed alongside Columbia, Brown and Yale University student assembly presidents, similar to the Resolution 35. [77] Despite these efforts and their claims regarding “any person…any study,” the Cornell administration has failed to eliminate inequitable practices. [78] The Cornell admissions website still maintains that “when two students with similar, strong credentials apply to Cornell, the applicant who is a child of a Cornell University alumna/alumnus may have a slight advantage in the admissions process.” [79]

Actively advocating for reparations and affirmative action in pursuit of inclusive education is crucial. Education shapes the minds of future generations, the next workforce, and the society we are building for a greater tomorrow. The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights highlighted that universities can still promote diversity through race-neutral means, including need-based financial aid, eliminating legacy admissions, and strengthening Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Access (DEIA) initiatives. [80] Yet, this case cannot be simplified as a mere legal decision without vast transformative precedent—it is a battle over the future of justice in America. As attacks on DEI intensify with new executive powers, the legal system’s role in shaping equality has never been more urgent.

Endnotes

[1] Julian Mark, Taylor Telford, and Emma Kumer, “Affirmative Action Is under Attack. How Did We Get Here?,” Washington Post, March 9, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/interactive/2024/dei-historyaffirmative-action-timeline/.

[2] Mark, Telford, and Kumer, “Affirmative Action Is under Attack. How Did We Get Here?”.

[3] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v President & Fellows of Harv. Coll., 600 U.S. 181, 201-202 [2023])

[4] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 202

[5] Regents of Univ. of California v Bakke, 438 US 265, 270 [1978]

[6] Regents of Univ. of California, 438 US 265, 269

[7] Regents of Univ. of California, 438 US 265, 269

[8] Regents of Univ. of California, 438 US 265, 269

[9] Grutter v Bollinger, 539 US 306, 311 [2003])

[10] Grutter, 539 US 306, 311.

[11] Grutter, 539 US 306, 311.

[12] Id., at 342, 123 S. Ct. 2325, 156 L. Ed. 2d 304.

[13] Id., at 342, 123 S. Ct. 2325, 156 L. Ed. 2d 304.

[14] Amy Howe, “Supreme Court Strikes down Affirmative Action Programs in College Admissions,” SCOTUSblog (SCOTUSblog, June 29, 2023), https://www.scotusblog.com/2023/06/supreme-court-strikes-down-affirmativeaction-programs-in-college-admissions/.

[15] Fisher v Univ. of Texas, 579 US 365, 371 [2016].

[16] Fisher, 579 US 365, 378.

[17] ProPublica, “What Abigail Fisher’s Affirmative Action Case Was Really About,” ProPublica (ProPublica, June 23, 2016), https://www.propublica.org/article/a-colorblind-constitution-what-abigail-fishers-affirmative-action-caseis-r.

[18] Fisher, 579 US 365, 366.

[19] Sarah Hinger, “Meet Edward Blum, the Man Who Wants to Kill Affirmative Action in Higher Education | News & Commentary,” American Civil Liberties Union, October 17, 2018, https://www.aclu.org/news/racial-justice/meetedward-blum-man-who-wants-kill-affirmative-action-higher. [20] Harvard University, “The History of Harvard,” Harvard University, 2023, https://www.harvard.edu/about/history/.

[21] Harvard College, “Admissions Statistics | Harvard College,” Harvard.edu, October 24, 2024, https://college.harvard.edu/admissions/admissions-statistics.

[22] Harvard College, “Admissions Statistics | Harvard College”.

[23] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 195.

[24] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 194.

[25] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 195.

[26] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 196-197.

[27] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 196.

[28] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 198.

[29] Students for Fair Admissions, “Students for Fair Admissions,” Students for Fair Admissions, accessed April 14, 2025, https://studentsforfairadmissions.org/about/.

[30] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 181

[31] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 197-198.

[32] Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, “SUMMARY of the SUPREME COURT’S DECISIONS in Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina (2023),” August 2023, https://www.lawyerscommittee.org/wpcontent/uploads/2023/08/LC_Harvard-UNC-Cases_D.pdf.

[33] Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, “Supreme Court Decisions”.

[34] Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, “Supreme Court Decisions”.

[35] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 211-212

[36] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 186 [37] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 186

[38] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 215

[39] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 216

[40] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 218

[41] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 218

[42] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 220

[43] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 213

[44] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 221

[45] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 222

[46] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 332

[47] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 318

[48] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 318 49 Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 337

[50] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc., 600 US 181, 361

[51] Cornell University Diversity and Inclusion, “Our Historic Commitment,” diversity.cornell.edu (Belonging at Cornell), accessed April 8, 2025, https://diversity.cornell.edu/our-story/our-historic-commitment.

[52] Blaine Friedlander, “At 150, ‘… Any Person … Any Study’ Still Stands Strong | Cornell Chronicle,” Cornell Chronicle, October 4, 2018, https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2018/10/150-any-person-any-study-still-stands-strong; Kaitlyn Danielle Ruhf, “To Do the Greatest Good: An Origin Story | Giving to Cornell | Cornell University,” Giving to Cornell | Cornell University, June 26, 2023, https://giving.cornell.edu/story/to-do-the-greatest-good-an-originstory/.

[53] Cornell University Diversity and Inclusion, “Our Historic Commitment”

[54] Melanie Lefkowitz, “Q&A: Cornell Releases Demographic Data for ‘Exceptional’ Incoming,” Cornell Chronicle, 2024, https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2024/09/qa-cornell-releases-demographic-data-exceptional-incoming-class.

[55] Cornell Chronicle “Q&A” ed. Melanie Lefkowitz

[56] Patricia Waldron and Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science, “Race-Blind College Admissions Harm Diversity without Improving Quality,” Cornell Chronicle, November 21, 2024, https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2024/11/race-blind-college-admissions-harm-diversity-without-improving-quality.

[57] Jinsook Lee et al., “Ending Affirmative Action Harms Diversity without Improving Academic Merit,” EAAMO ’24: Proceedings of the 4th ACM Conference on Equity and Access in Algorithms, Mechanisms, and Optimization 8 (October 23, 2024): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1145/3689904.3694706.

[58] Jinsook Lee et al., “Ending Affirmative Action Harms Diversity without Improving Academic Merit,” 1–17.

[59] The White House, “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity – the White House,” The White House, January 21, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/ending-illegaldiscrimination-and-restoring-merit-based-opportunity/.

[60] News Department, “Trump’s Executive Orders Spark Concern over Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at Cornell,” The Cornell Daily Sun, February 3, 2025, https://www.cornellsun.com/article/2025/02/trumps-executive-ordersspark-concern-over-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-at-cornell.

[61] Craig Trainor, “United States Department of Education Office for Civil Rights the Acting Assistant Secretary,” February 14, 2025, https://www.ed.gov/media/document/dear-colleague-letter-sffa-v-harvard-109506.pdf.

[62] Trainor, “United States Department of Education Office for Civil Rights the Acting Assistant Secretary”

[63] Trainor, “United States Department of Education Office for Civil Rights the Acting Assistant Secretary”

[64] Benjamin Leynse, “Department of Education Orders Academic Institutions to End All Race-Based Programs within Two Weeks,” The Cornell Daily Sun, February 19, 2025, https://www.cornellsun.com/article/2025/02/department-of-education-orders-academic-institutions-to-end-all-racebased-programs-within-two-weeks.

[65] Emma Galgano, “Cornell Restores DEI References, Resources and Maintains Omission of Affirmative Action in Equal Opportunity Statement,” Cornell Restores DEI References, Resources and Maintains Omission of Affirmative Action in Equal Opportunity Statement - The Cornell Daily Sun, March 21, 2025, https://www.cornellsun.com/article/2025/03/cornell-restores-dei-references-resources-and-maintains-omission-ofaffirmative-action-in-equal-opportunity-statement.

[66] Galgano, “Cornell Restores DEI References”

[67] Galgano, “Cornell Restores DEI References”

[68] Jeremiah Jung, “Father and Son Sue Cornell, Alleging Racial Discrimination in Admissions,” Father and Son Sue Cornell, Alleging Racial Discrimination in Admissions - The Cornell Daily Sun, March 27, 2025, https://www.cornellsun.com/article/2025/03/father-and-son-sue-cornell-alleging-racial-discrimination-inadmissions.

[69] Civil Rights Litigation Clearing House, “Zhong v. Cornell University 3:25-Cv-00365 (N.D.N.Y.) | Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse,” Clearinghouse.net, March 22, 2025, https://clearinghouse.net/case/46311/.

[70] Jung, “Father and Son Sue Cornell”.

[71] Patriot Act. “Affirmative Action | Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj | Netflix.” YouTube, October 28, 2018. 21:08- 21:20. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zm5QVcTI2I8.

[72] SciencesPo, “The Value of Diversity: Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s 2009 Keynote Speech,” Sciences Po, September 23, 2020, https://www.sciencespo.fr/en/news/the-value-of-diversity-ruth-bader-ginsburg-at-the-2009-graduationceremony/.

[73] SciencesPo, “The Value of Diversity: Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s 2009 Keynote Speech.”

[74] Greg Rosalsky, “Affirmative Action for Rich Kids: It’s More than Just Legacy Admissions,” NPR, July 24, 2023, https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2023/07/24/1189443223/affirmative-action-for-rich-kids-its-more-than-justlegacy-admissions.

[75] Raj Chetty, David Deming, and John Friedman, “Diversifying Society’s Leaders? The Causal Effects of Admission to Highly Selective Private Colleges,” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2023, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4542762.

[76] Rosalsky, “Affirmative Action for Rich Kids: It’s More than Just Legacy Admissions”.

[77] Eric Lechpammer, “Student Assembly Unanimously Passes Resolution Urging End to Legacy Admissions,” Student Assembly Unanimously Passes Resolution Urging End to Legacy Admissions - The Cornell Daily Sun, March 25, 2024, https://www.cornellsun.com/article/2024/03/student-assembly-unanimously-passes-resolutionurging-end-to-legacy-admissions.

[78] Friedlander, “At 150, ‘… Any Person … Any Study’ Still Stands Strong”.

[79] Cornell University Undergraduate Admissions Office, “Do Applicants Who Are Direct Descendants of Cornell University Graduates Have a Better Chance of Admission?,” Cornell University, 2020, https://faq.enrollment.cornell.edu/kb/article/49-do-applicants-who-are-children-of-cornell-university-graduateshave-a-better-chance-of-admission/.

[80] Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, “Supreme Court Decisions”.